In this article, we will try to understand what useLayoutEffect is. I will attempt to demonstrate that you probably should:

useEffect whenever possible to streamline the user experience.useLayoutEffect whenever you need to run effects before the visual is painted to modify it.So let’s get into it!

figure { text-align: center; margin-block: 4rem; } figure > figcaption { opacity: 80%; font-size: .8em; }

Recently I have been very busy with accessibility features for my projects. It really is a fascinating subject and there definitely is a lot to learn. But the first thing you really need to learn is handling the focus with the keyboard for your components because, not only some people can’t use a mouse when browsing, but some people might also just prefer using the keyboard to navigate.

useEffect allows you to run asynchronous side effects in your component. With its second argument, a dependency array, it is very useful for fetching data and using callbacks on state change.

You can learn more about useEffect in the official documentation.

Unlike useEffect, useLayoutEffect runs synchronously after any DOM mutation — when React modifies the DOM during a render — but before the browser paints the page.

Figure 1. useEffect render timeline

Figure 2. useEffect render timeline on displayed page

Even though it is enticing to only use layout effects, it is strongly advised you start with useEffect and switch to useLayoutEffect only if necessary because any code that runs in the latter will cause the paint to be delayed. One of the use cases for layout effects is changing the content or layout of the page since regular effects could cause flickering:

Figure 3. Flickering page timeline with useEffect

By using useLayoutEffect instead of useEffect, the page will take longer to render but it will directly render with the meaningful content, removing the flicker effect of the multiple paints.

Figure 4. Flickering page timeline with useLayoutEffect

When you refresh the following sandbox, notice how the page renders the unmodified data for a fraction of a second before updating to the modified version with useEffect:

.warn, .info { display: flex; align-items: center; font-family: -apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, "Segoe UI", Roboto, Oxygen-Sans, Ubuntu, Cantarell, "Helvetica Neue", sans-serif; border-radius: 1ch; } .info { background: lightblue; } .warn { background: rgb(255 233 186); } .warn > .icon, .info > .icon { margin: 1ch; font-size: 1.5rem; } .warn > p, .info > p { margin: 1ch; }

ℹ

You might not be able to see the example below flicker if your computer manages to set the state before your browser paints the result.

https://codesandbox.io/s/useeffect-flicker-example-5uof2?from-embed

Figure 5. Flicker slowed down to 10% of base speed

In the example below using a layout effect, notice how the page is rendered directly with the modified data:

https://codesandbox.io/s/uselayouteffect-flicker-example-u98yt?from-embed

You can learn more about useLayoutEffect in the official documentation and in this article by Kent C. Dodds.

A small disclaimer, for the remainder of this article, we will only talk about focus and keyboard control but the topic of accessibility is way vaster, ranging from aria properties to roving tabindex and so much more. If you want to learn more about general accessibility, the official documentation from the W3C is an invaluable source of information provided you have some time on your hands.

Did you know that your operating system is probably entirely usable without a mouse? On Windows and MacOS, you can navigate any shortcut using only the Tab key. Then, inside an application, a combination of Alt on Windows, ^+F2 on MacOS and arrow keys allows you to reach any menu. This is not just to be fancy, this is actually necessary for some people who can’t use a mouse. If any link or button on your page is not reachable using only the keyboard, it means that a portion of the users — and it is not just the people with a permanent disability, consider for instance someone with a temporarily broken arm or mouse — won’t be able to access it.

Even though setting the tabindex attribute to 0 is sufficient to make any part of the application accessible, since it will add the element to the tab order, allowing it to be reached using the Tab key, it will still make the application very hard to use for someone with a disability. For your component to “feel native” and to facilitate the interaction with your components, you will need to implement keyboard controls:

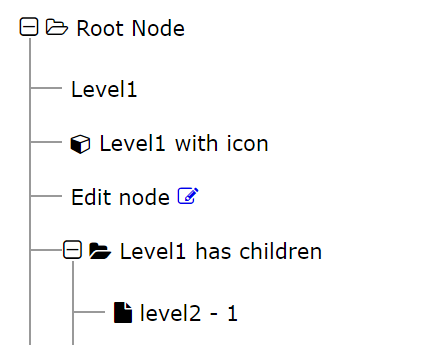

Consider, for example, a screen reader user operating a tree [component].

Figure 6. Example of a tree component

Just as familiar visual styling helps users discover how to expand a tree branch with a mouse, ARIA attributes give the tree the sound and feel of a tree in a desktop application. So, screen reader users will commonly expect that pressing the right arrow key will expand a collapsed node. Because the screen reader knows the element is a tree, it also has the ability to instruct a novice user how to operate it. Similarly, voice recognition software can implement commands for expanding and collapsing branches because it recognizes the element as a tree and can execute appropriate keyboard commands.

To expand on this tree example, a user might expect that pressing down arrow would move the focus to the next item, or pressing a character key would jump the focus to the next matching element, so now we need to implement a keyboard handler that takes these use cases into consideration. And since we need to instruct a screen reader that the focus jumped, we can’t implement our own version of focus() with some state and css classes. We need to use the built-in focus().

There is no “React specific“ way of giving focus to a component since plain JavaScript allows us to do so very easily:

.wp-block-code {border: 1px solid black;}

const input = document.getElementById('my-input')

input.focus()

So now the question is “How does it translate to React and its components?“.

We could technically still use document.getElementById():

function MyComponent() {

const thisComponent = document.getElementById('my-component')

thisComponent?.focus()

return (

<button type="button" id="my-component">Click Me!</button>

)

}

But now we can only render this component once or we would have twice the same ID in our DOM, which is not allowed.

⚠️

Refs are usually not recommended for anything that is achievable declaratively.

A ref is essentially just a reference to some data that is shared between render instances but it can be used very effectively to reach the actual DOM element rendered by a React component:

import React, { useRef, useEffect } from 'react'

function App() {

const buttonRef = useRef<HTMLButtonElement>(null)

useEffect(() => {

// buttonRef.current instanceof HTMLButtonElement --> true

}, [buttonRef])

return (

<button type="button" ref={buttonRef}>Click Me!</button>

)

}

Now, giving focus to the button is just plain JavaScript (or in this case TypeScript):

function App() {

const buttonRef = useRef<HTMLButtonElement>(null)

useEffect(() => {

ref.current?.focus()

}, [])

return (

<button type="button" ref={buttonRef}>Click Me!</button>

)

}

This far, I told you to avoid using layout effects when possible and now I’m telling you to use them when a regular effect seems to work?! I promise, I’m not just making things up: I would recommend using a layout effect in this instance because, when giving focus to an element, if not explicitly prevented, the browser will automatically scroll the element to view:

https://codesandbox.io/s/young-monad-sot2t?from-embed

This may cause the page to flicker if focus() is called on an element that is below the fold line since the viewport will jump to that element after the page is first painted:

https://codesandbox.io/s/jumping-focus-with-useeffect-r8xi5?from-embed

Figure 7. Flicker slowed down to 10% of base speed

This can be prevented with layout effects since the focus will already be on the last element when the browser paints the page:

https://codesandbox.io/s/jumping-focus-with-uselayouteffect-ubtiq?from-embed

The difference with handling focus is the asynchronicity of the network:

Figure 8. Timeline of an asynchronous fetch

At this point, your layout effect will create a Promise that will resolve long after the paint is done so you will delay your paint to create the Promise but it will not wait for your promise to resolve before painting. Using a layout effect in this case is detrimental since it will delay the paint but will not prevent the second render after the Promise resolves.

In contrast, using a layout effect to modify synchronously your DOM will prevent flickering:

.info { background: lightblue; display: flex; align-items: center; font-family: -apple-system, BlinkMacSystemFont, "Segoe UI", Roboto, Oxygen-Sans, Ubuntu, Cantarell, "Helvetica Neue", sans-serif } .warn > .icon { margin: 1ch; font-size: 1.5rem; } .info > .icon { margin: 1ch; font-size: 1.5rem; }

ℹ

Note that this use case is very limited, consider using your synchronous effect as the base value for your initial DOM mutation — e.g. as the default value for your state — to avoid mutating twice.

Figure 9. Timeline of a synchronous layout effect

And since focussing an element is not a DOM mutation, we don’t need to loop back on the DOM mutation step:

Figure 10. Timeline of a focus call in a layout effect

We made it!

Let’s sum up:

useEffect whenever possible.useLayoutEffect whenever you need to run effects before the visual is painted.From the moment you start adding accessibility features to your application, you will need to manually handle the focus. Here is a snippet of code to help you:

function MyComponent() {

const ref = useRef()

useLayoutEffect(() => {

if (shouldFocus) {

ref.current?.focus()

}

}, [shouldFocus])

return (

...

)

}

Now this might get copy-pasted often so I’ll do you one better: what if we added a level of abstraction?

function MyComponent() {

const ref = useFocus(shouldFocus)

return (

...

)

}

function useFocus(shouldFocus) {

const ref = useRef()

useLayoutEffect(() => {

if (shouldFocus) {

ref.current?.focus()

}

}, [shouldFocus])

return ref

}