We propose a “Quick Reference Card”, as a summary of best practices in REST API design.

➡ Download API Design – Quick Reference Card

As soon as we start working on an API, design issues arise. A robust and strong design is a key factor for API success. A poorly designed API will indeed lead to misuse or - even worse - no use at all by its intended clients: application developers.

Creating and providing a state of the art API requires taking into account:

Nowadays, two opposing approaches are seen.

“Purists” insist upon following REST principles without compromise. “Pragmatics” prefer a more practical approach, to provide their clients with a more usable API. The proper solution often lies in between.

Designing a REST API raises questions and issues for which there is no universal answer. REST best practices are still being debated and consolidated, which is what makes this job fascinating.

To facilitate and accelerate the design and development of your APIs, we share our vision and beliefs with you in this article. They come from our direct experience on API projects.

DISCLAIMER : This article is a collection of best practices meant to be discussed. We invite you to discuss and challenge them on our blog.

One of the objectives of an API strategy is to reach out to as many developers as possible, opening one’s system to the Internet. It is therefore critical that the API be self-describing and as simple as possible, so that developers barely need to refer to the documentation. We refer to this as affordance: the API suggests its own usage.

When designing an API, the following principles should be kept in mind:

➡ Which “Blender” is the simplest ?

➡ Which “Blender” is the simplest ?

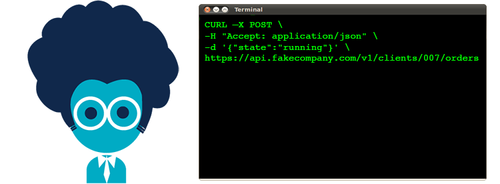

cURL examples are widely used to illustrate API calls: the Web Giants do it, as does technical literature in general.

We recommend always illustrating your API call documentation by cURL examples. Readers can simply cut-and-paste them, and they remove any ambiguity regarding call details.

➡ Example

CURL –X POST \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

-d '{"state":"running"}' \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders

The “one resource = one URL” theory tends to increase the number of resources. It’s important to keep a reasonable limit.

For instance : a person contains an address that in turn contains a country.

It’s important to avoid making 3 API calls...

CURL https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/users/1234

< 200 OK

< {"id":"1234", "name":"Antoine Jaby", "address":"https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/addresses/4567"}CURL https://api.fakecompany.com/addresses/4567

< 200 OK

< {"id":"4567", "street":"sunset bd", "country": "http://api.fakecompany.com/v1/countries/98"}CURL https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/countries/98

< 200 OK

< {"id":"98", "name":"France"}

…especially since these 3 pieces of information are commonly used together. This could lead to performance issues.

On the other hand, accumulating too much information a priori is likely to make API calls and exchanges too verbose.

Designing an API with an optimal granularity is not straightforward. It is often cultural and is the result of past API design experiences. In doubt, try to avoid exchanges becoming too big or too specific.

Grouping only resources that are almost always accessed together

Not embedding collections having many components. For example, a list of current jobs is limited (it’s difficult to have more than 2 or 3 jobs at the same time) but a list of past work experiences can be much longer.

Having at most 2 levels of nested objects (e.g. /v1/users/addresses/countries)

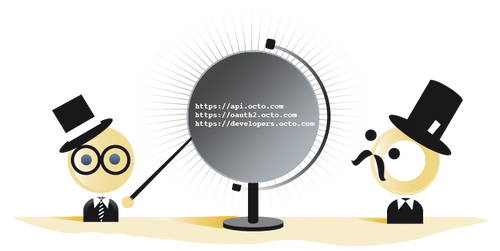

In terms of domain names, All Web Giants don’t have the same practices. Some of them, such as Dropbox, use several domains or subdomains for their APIs.

➡ Below are a few Web Giants examples

To normalize domain names while keeping affordance in mind, we recommend using only 3 subdomains for your production environment :

This subdivision is intended to help developers easily figure out how to:

Some Web Giants, like Paypal, also provide a sandbox environment, which is very useful for testing the API before using it live on the production environment:

https://developer.paypal.com/docs/api/

We recommend using 2 subdomains for your sandbox environment :

Two protocols are widely used to secure REST APIs:

➡ What about the Web Giants?

| OAuth1 | OAuth2 |

| Twitter, Yahoo, flickr, tumblr, Netflix, myspace, evernote,… | Google, Facebook, Dropbox, GitHub, amazon, Intagram, LinkedIn, foursquare, salesforce, viadeo, Deezer, Paypal, Stripe, huddle, boc, Basecamp, bitly,… |

| MasterCard, CA-Store, OpenBankProject, intuit,… | AXA Banque, Bouygues telecom,… |

We recommend securing your API with OAuth2.

With regard to OAuth2 token validation, we recommend implementing Google’s solution, implicit grant flow:

We recommend always using HTTPS wwhen communicating with :

To validate your OAuth2 implementation, you might want to try the following test:

If it works, you’re good to go !

To describe your resources, we recommend you use concrete names and not action verbs.

For decades, computer scientists used action verbs in order to expose services in an RPC way, for instance:

By contrast, the RESTful approach is to use:

Using HTTP as the application protocol is one of the core goals of a REST API. It adds consistency and facilitates interactions between information systems. It also keeps us from reinventing the wheel with a homemade SOAP/RPC/EJB-like protocol.

It is acknowledged that HTTP verbs be used to describe what actions are performed on resources (see topic CRUD).

the use of these HTTP verbs makes an API more intuitive and helps developers understand how to manipulate resources without having to look at verbose documentation, therefore enhancing the API’s affordance.

In practice, developers tools also help them generate HTTP requests with appropriate verbs and payloads based on an up to date object model.

Most of the time, Web Giants have a consistent behavior with regard to resource names being singular or plural. Indeed, the main concern is not to mix them: having resource names vary between singular and plural reduces the “browsability” of the API.

Resource names seem more natural to us when they are set to plural, in order to address collections and instances of resources with consistency.

Thus, we recommend the plural form for 2 types of resources:

As an example, for the creation of a user we will consider that POST /v1/users is the call of the create action on the users collection. Likewise, GET /v1/users/007 to retrieve a user can be understood as “I want user 007 in the users collection”

When it comes to naming resources in a program, there are 3 main types of case conventions: CamelCase, snake_case, and spinal-case. They are just a way of naming the resources to resemble natural language, while avoiding spaces, apostrophes and other exotic characters. This habit is universal in programming languages where only a finite set of characters is authorized for names.

These 3 cases have their variants, based on criteria such as first letter case, behavior with accents or other special characters. Using English is recommended, to avoid special characters.

According to RFC3986, URLs are “case sensitive” (except for the scheme and the host). In practice, though, a sensitive case may create dysfunctions with APIs hosted on a Windows system.

Here is a digest of the Web Giants’ practices:

| Paypal | Amazon | dropbox | github | ||||

| snake_case | x | x | x | x | x | ||

| spinal-case | x | x | |||||

| camelCase | x |

Regarding the URIs, we recommend choosing a consistent case convention between:

➡ Examples

POST /v1/specific-orders

or

POST /v1/specific_orders

There are two main formats regarding the data body.

On the first hand, the snake_case is used noticeably more by Web Giants, in particular it has been adopted by OAuth2 specifications. On the other hand, the growing popularity of the JavaScript language contributes to the camelCase adoption, even if theoretically, REST should remain language independent and expose a state-of-the-art API over XML.

We advise you to use a consistent case for the body, to be chosen between:

➡ Examples

GET /orders?id_client=007 or GET /orders?idClient=007

POST /orders {"id_client":"007"} or POST /orders {"idClient":"007”}

Any API will have to evolve over time. There are several ways of versioning an API:

➡ In practice by the Web Giants:

We recommend including a compulsory one digit version at the highest level of the URI’s path.

➡ Example

GET /v1/orders

As stated earlier, one of the key objectives of the REST approach is using HTTP as an application protocol in order to avoid shaping a homemade API.

Hence, we should systematically use HTTP verbs to describe what actions are performed on the resources and facilitate the developer’s work handling recurrent CRUD operations. The following table synthesizes the best practices usually observed:

| HTTP Verb | CRUD action | Collection : /orders | Instance : /orders/{id} |

| GET | READ | Read a list of orders. 200 OK. | Read the detail of a single order. 200 OK. |

| POST | CREATE | Create a new order. 201 Created. | - |

| PUT | UPDATE/CREATE | - | Full Update. 200 OK. Create a specific order. 201 Created. |

| PATCH | UPDATE | - | Partial Update. 200 OK. |

| DELETE | DELETE | - | Delete order. 200 OK. |

The HTTP verb POST is used to create an instance within a collection. The id of the resource to be created does not need to be provided.

CURL –X POST \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"state":"running","id_client":"007"}' \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders

< 201 Created

< Location: https://api.fakecompany.com/orders/1234

The return code is 201 rather than 200.

The resource URI and id are sent back in the header “Location” of the response.

If the resource id is specified by the client, the HTTP verb PUT is used for the creation of an instance within the collection. However, in practice this use case is less frequent.

CURL –X PUT \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"state":"running","id_client":"007"}' \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders/1234

< 201 Created

The HTTP verb PUT is consistently used in order to do a full update of an instance in the collection (all attributes are replaced and those which do not exist are deleted).

In the example below, we update the attributes state and id_client. All the other fields will be deleted.

CURL –X PUT \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"state":"paid","id_client":"007"}' \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders/1234

< 200 OK

The HTTP verb PATCH (which was missing in the initial HTTP specifications and was added later on) is commonly used for partial update of an instance within a collection.

In the following example, we update the state attribute but the other attributes are left untouched.

CURL –X PATCH \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"state":"paid"}' \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders/1234

< 200 OK

The HTTP verb GET is used to read a collection. In practice, the API generally does not return all the collection items (see section Paging).

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders

< 200 OK

< [{"id":"1234", "state":"paid"}, {"id":"5678", "state":"running"}]

The HTTP verb GET is used to read an instance in a collection.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/clients/007/orders/1234

< 200 OK

< {"id":"1234", "state":"paid"}

Partial answers allow clients to retrieve only the information they need. This feature is vital in mobile contexts (UMTS-) where bandwidth usage must be optimized.

➡ At the Web Giants':

| API | Partial responses |

| ?fields=url,object(content,attachments/url) | |

| &fields=likes,checkins,products | |

| https://api.linkedin.com/v1/people/~:(id,first-name,last-name,industry) |

We recommend at least being able to select the attributes to be retrieved, over 1 level of resource, through the Google notation fields=attribute1,attributeN:

GET /clients/007?fields=firstname,name

200 OK

{

"id":"007",

"firstname":"James",

"name":"Bond"

}

In contexts where performance is a strong concern, we propose using the Google notation fields=objects(attribute1,attributeN). As an example, if we want to retrieve only the first name, last name, and the street of a client’s address:

GET /clients/007?fields=firstname,name,address(street)

200 OK

{

"id":"007",

"firstname":"James",

"name":"Bond",

"address":{"street":"Horsen Ferry Road"}

}

It is necessary to anticipate the paging of your resources in the early design phase of your API. It is indeed difficult to foresee precisely the progression of the amount of data that will be returned. Therefore, we recommend paginating your resources with default values when they are not provided by the calling client, for example with a range of values [0-25].

Systematic pagination also brings cohesion to your resources, which is good. Bear in mind the affordance principle: the less documentation developers have to read, the easier their appropriation.

➡ At the Web Giants':

| API | Pagination |

Parameters : before, after, limit, next, previews<br><br><br>"paging": {<br>"cursors": {<br>"after": "MTAxNTExOTQ1MjAwNzI5NDE=",<br>"before": "NDMyNzQyODI3OTQw"<br>},<br>"previous": "https://graph.facebook.com/me/albums?limit=25&before=NDMyNzQyODI3OTQw"<br>"next": "https://graph.facebook.com/me/albums?limit=25&after=MTAxNTExOTQ1MjAwNzI5NDE="<br>}<br> | |

Parameters : maxResults, pageToken<br><br><br>"nextPageToken":"CiAKGjBpNDd2Nmp2Zml2cXRwYjBpOXA",<br> | |

Parameters : since_id, max_id, count<br><br><br>"next_results": "?max_id=249279667666817023&q=*freebandnames&count=4&include_entities=1&result_type=mixed",<br>"count": 4,<br>"completed_in": 0.035,<br>"since_id_str": "24012619984051000",<br>"query": "*freebandnames",<br>"max_id_str": "250126199840518145"<br> | |

| GitHub | Parameters : page, per_page<br><br><br>Link: <https://api.github.com/user/repos?page=3&per_page=100>; rel="next",<br><https://api.github.com/user/repos?page=50&per_page=100>; rel="last"<br> |

| Paypal | Parameters : start_id, count<br><br><br>{'count': 1,'next_id': 'PAY-5TU010975T094876HKKDU7MZ',<br> |

Various paging mechanisms are used by the Web Giants. As no shared standard seems to emerge, we propose using:

➡ Pagination in the request

From a practical point of view, pagination is often managed in the URL through the query-string. HTTP headers also provide this mechanism. We propose only accepting the query-string way, and not taking into account the Range HTTP Header. Pagination is an important piece of information, it makes sense to have it in the request for the sake of affordance.

We propose that you use a range of values through your collection’s resources index. As an example, resources from index 10 to 25 included is equivalent to ?range=10-25.

➡ Pagination in the answer

The HTTP code returned by a paginated request will be 206 Partial Content, except if the requested values cause the return of the whole collection’s data, in which case the return code will be 200 OK.

Your API response for a collection must provide in the HTTP Headers:

Content-Range offset - limit / count

Accept-Range resource max

In the event of a requested pagination not fitting the values permitted by the API, the HTTP answer should be a 400 error code with an explicit description of the error in the body.

➡ Navigation links

It is highly recommended to include the Link tag in the HTTP Header of your answers. It allows you to add, amongst others, navigation links such as next page, previous page, first and last page…

➡ Examples

We have in our API a collection of 48 restaurants, for which you can only request 50 elements at a time. The default pagination is 0-50:

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants

< 200 Ok

< Content-Range: 0-47/48

< Accept-Range: restaurant 50

< [...]

If 25 resources are requested of the 48 available, we receive a 206 Partial Content return code:

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?range=0-24

< 206 Partial Content

< Content-Range: 0-24/48

< Accept-Range: restaurant 50

If 50 resources are requested of the 48 available, a 200 OK return code is returned:

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?range=0-50

< 200 Ok

< Content-Range: 0-47/48

< Accept-Range: restaurant 50

If the requested range is greater than the maximum number of resources for a single request (Header Accept-Range), a 400 Bad Request code is returned:

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=0-50

< 400 Bad Request

< Accept-Range: order 10

< { reason : "Requested range not allowed" }

We recommend using the following notation for returning links to other ranges. It is used by GitHub and is compatible with the RFC5988. It also allows to manage clients which do not support several Link Headers.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=48-55

< 206 Partial Content

< Content-Range: 48-55/971

< Accept-Range: order 10

< Link : <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=0-7>; rel="first", <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=40-47>; rel="prev", <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=56-64>; rel="next", <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=968-975>; rel="last"

Another notation is frequently encountered, with a HTTP Header tag Link containing an URL followed by the type of the link. This tag can be repeated as many times as there are links associated with the answer:

< Link: <https:<i>//api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=0-7>; rel="first"</i>

< Link: <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=40-47>; rel="prev"

< Link: <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=56-64>; rel="next"

< Link: <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=968-975>; rel="last"

Or the following notation in the payload, which is used by Paypal :

[

{"href":"https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=0-7", "rel":"first", "method":"GET"},

{"href":"https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=40-47", "rel":"prev", "method":"GET"},

{"href":"https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=56-64", "rel":"next", "method":"GET"},

{"href":"https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders?range=968-975", "rel":"last", "method":"GET"},

]

Filtering consists in restricting the number of queried resources by specifying some attributes and their expected values. It is possible to filter a collection on several attributes at the same time, and to allow several values for one filtered attribute.

We propose to use directly the attribute’s name with an equal sign and the expected values, each of them separated by a comma.

Example : retrieve thai food restaurants

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?type=thai

Example: retrieve restaurants with a 4 or 5 rating, proposing Chinese or Japanese food and open on sundays

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?type=japanese,chinese&rating=4,5&days=sunday

Sorting the result of a query on a collection of resources requires two main parameters:

Example: retrieving the list of restaurants sorted by name

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?sort=name

Example: retrieving the list of restaurants, sorted by descending rating, then by ascending review count, and finally by ascending name.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?sort=rating,reviews,name&desc=rating,reviews

➡ Sorting, Filtering and Paging

Paging is very likely to be impacted by sorting and filtering. The combination of these 3 parameters should be usable with consistency in the requests to your API

Example: Request of the first five Chinese restaurants sorted by descending rating.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants?type=chinese&sort=rating,name&desc=rating&range=0-4

< 206 Partial Content

< Content-Range: 0-4/12

< Accept-Range: restaurants 50

If filtering does not fit our needs (to make partial or approximate matches, for instance), we need the ability to search the available resources.

A search is a sub-resource of our collection. As such, its results will have a different format than the resources and the collection itself. This allows us to add suggestions, corrections and information related to the search.

Parameters are provided the same way as for a filter, through the query-string, but they are not necessarily exact values, and their syntax permits approximate matching.

Being itself a resource, the search must support paging like all the other resources of your API.

Example: searching for restaurants whose names start with “La”.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants/search?name=la*

< 206 Partial Content

< { "count" : 5, "query" : "name=la*", "suggestions" : ["las"], results : [...] }

Example: Searching for the first 10 restaurants with a name containing “Napoli”, which cook Chinese or Japanese food, located in Paris (zip code 75), sorted by descending rating and name.

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

-H "Range 0-9" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/restaurants/search?name=*napoli*&type=chinese,japanese&zipcode=75*&sort=rating,name&desc=rating&range=0-9

< 206 Partial Content

< Content-Range: 0-9/18

< Accept-Range: search 20

< { "count" : 18, "range": "0-9", "query" : "name=*napoli*&type=chinese,japanese&zipcode=75*", "suggestions" : ["napolitano", "napolitain"], results : [...] }

Global search should have the same behavior as resource-specific search, except that it is located at the root of the API and therefore must be pointed out in the documentation.

We recommend Google’s notation for global searches:

CURL –X GET \

-H "Accept: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/search?q=running+paid

< [...]

We recommend handling several content distribution formats. We can use the HTTP Header dedicated to this purpose: “Accept”.

By default, the API will share resources in the JSON format, but if the request begins with “Accept: application/xml”, resources should be sent in the XML format.

It is recommended to manage at least 2 formats: JSON and XML. The order of the formats queried by the header “Accept” must be observed to define the response format.

In cases where it is not possible to supply the required format, a 406 HTTP Error Code is sent (cf. Errors — Status Codes).

GET https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/offers

Accept: application/xml; application/json XML préféré à JSON

< 200 OK

< [XML]GET https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/offers

Accept: text/plain; application/json The API cannot provide text

< 200 OK

< [JSON]

When the application (JavaScript SPA) and the API are hosted on different domains, for example:

A good practice consists in using the CORS protocol which is the HTTP standard.

On the server side, CORS implementation usually consists in adding a few instructions in HTTP servers (Nginx/Apache/NodeJs…).

On the client side, implementation is imperceptible: the browser will send a HTTP request with the OPTIONS verb before any GET/POST/PUT/PATCH/DELETE request.

Here follows an example of two successive calls made by a browser in order to retrieve, through GET, information of a user with the Google+ API:

CURL -X OPTIONS \

-H 'Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8' \

'https://www.googleapis.com/plus/v1/people/105883339188350220174?client_id=API_KEY'

CURL -X GET\

'https://www.googleapis.com/plus/v1/people/105883339188350220174?client_id=API_KEY' \

-H 'Accept: application/json, text/JavaScript, */*; q=0.01'\

-H 'Authorization: Bearer foo_access_token'

In fact, CORS is either badly or not at all supported by old browsers, especially IE7, 8, and 9. If your API is to be used by browsers which you do not control (on the Internet, with customers), it is still necessary to propose a Jsonp exposition of your API as a fallback of the CORS implementation.

Indeed, Jsonp is a work-around of the tag usage aimed at allowing the cross-domain management:

To be CORS & Jsonp compliant, as an example, your API should expose the following endpoints:

POST /orders and /orders.jsonp?method=POST&callback=foo

GET /orders and /orders.jsonp?callback=foo

GET /orders/1234 and /orders/1234.jsonp?callback=foo

PUT /orders/1234 and /orders/1234.jsonp?method=PUT&callback=foo

Let’s take Angelina Jolie as an example. Angelina is an Amazon customer, and she wishes to read the details of her last order. To do this, she has two steps to follow:

On the Amazon website, Angelina does not need to be a web expert to read her last order: she just has to log-in into her account, then click on the “my orders” link and finally select the most recent one.

Now let’s imagine Angelina wishes to use an API to do the same thing!

She must begin by reading Amazon documentation to find the URL that returns her list of orders. When she finds it, she must make an actual HTTP call to this URL. She’ll see the reference of her order in the list, but she’ll need to make a second call to another URL to get its details. Angelina will have to figure out how to construct the proper URL from Amazon's documentation.

There is one main difference between these two scenarii: In the first one, Angelina just needed to know the first URL “http://www.amazon.com” then follow the links on the web page. Whereas in the second one, Angelina needed to read the documentation so as to elaborate the URL.

The drawbacks of the second process are:

Let’s assume Angelina develops a component to automatically create these contextual URLs. What happens when Amazon modifies its base URLs?

Implementation

In practical, HATEOAS is like a urban legend. Everybody talks about it but nobody ever witnessed an actual implementation.

Paypal proposes one:

[

{

"href": "https://api.sandbox.paypal.com/v1/payments/payment/PAY-6RV70583SB702805EKEYSZ6Y",

"rel": "self",

"method": "GET"

},

{

"href": "https://www.sandbox.paypal.com/webscr?cmd=_express-checkout&token=EC-60U79048BN7719609",

"rel": "approval_url",

"method": "REDIRECT"

},

{

"href": "https://api.sandbox.paypal.com/v1/payments/payment/PAY-6RV70583SB702805EKEYSZ6Y/execute",

"rel": "execute",

"method": "POST"

}

]

A call to /customers/007 would then return the details of the customer, along with pointers towards linked resources :

GET /customers/007

< 200 Ok

< { "id":"007", "firstname":"James",...,

"links": [

{"rel":"self","href":"https://api.domain.com/v1/customers/007", "method":"GET"},

{"rel":"addresses","href":"https://api.domain.com/v1/addresses/42", "method":"GET"},

{"rel":"orders", "href":"https://api.domain.com/v1/orders/1234", "method":"GET"},

...

]

}

For implementing HATEOAS, we therefore recomment using the following method, applied by GitHub, compliant with RFC5988 and usable by clients that don’t support several Header “Link”:

GET /customers/007

< 200 Ok

< { "id":"007", "firstname":"James",...}

< Link : <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/customers>; rel="self"; method:"GET",

< <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/addresses/42>; rel="addresses"; method:"GET",

< <https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/orders/1234>; rel="orders"; method:"GET"

In RESTFul theory, any request must be seen and manipulated as a resource. In real life, it’s not always possible, especially when we have to deal with actions such as translations, computations, conversions, complex business services or strongly integrated services.

In these cases, your operation must be represented by a verb rather than a name. For instance :

POST /calculator/sum

[1,2,3,5,8,13,21]

< 200 OK

< {"result" : "53"}

Or else :

POST /convert?from=EUR&to=USD&amount=42

< 200 OK

< {"result" : "54"}

We therefore come to use actions instead of resources. In this context, we will use the HTTP POST method.

CURL –X POST \

-H "Content-Type: application/json" \

https://api.fakecompany.com/v1/users/42/carts/7/commit

< 200 OK

< { "id_cart": "7",<i> [...] <i> }</i></i>

To design properly this exception in your API, the simplest solution is to consider that any POST request is an action with an implicit or explicit verb.

For a collection of entity resources for instance, the default action is a creation:

POST /users/create POST /users

< 201 OK == < 201 OK

< { "id_user": 42 } < { "id_user": 42 }

Or for an email resource, the default action will be to send it to its recipient.

POST /emails/42/send POST /emails/42I

< 200 OK == < 200 OK

< { "id_email": 42, "state": "sent" } < { "id_email": 42, "state": "sent" }

However, it is important to bear in mind that explicitly specifying a verb in your API design must remain an exception. In most cases, it can and must be avoided. If several resources expose one action or more, your API design is flawed: you took an RPC approach rather than a REST approach, and need to quickly take action by going over your API design.

In order to avoid any confusion in developers' minds between resources (which you can access the CRUD way) and actions, it is highly recommended to clearly separate these two concepts in the developer documentation.

➡ Web Giants examples

| API | “Non Resources” API |

| Google Translate API | GET https://www.googleapis.com/language/translate/v2?key=INSERT-YOUR-KEY&target=de&q=Hello%20world |

| Google Calendar API | POST https://www.googleapis.com/calendar/v3/calendars/calendarId/clear |

| Twitter Authentication | GET https://api.twitter.com/oauth/authenticate?oauth_token=Z6eEdO8MOmk394WozF5oKyuAv855l4Mlqo7hhlSLik |

We recommend the following JSON structure:

{

"error": "short_description",

"error_description": "longer description, human-readable,

"error_uri": "URI to a detailed error description on the API developer website "

}

The error attribute is not necessarily redundant with the HTTP status: we may have two different values for the error key while keeping the same HTTP status.

This representation is taken from the OAuth2 specification. A systematic use of this syntax in the API will prevent the clients from having to manage two distinct error structures.

Nota Bene: In some cases, it may be relevant to provide a collection of this structure in order to return several errors at the same time (this is useful in the case of a server-side form validation as an example).

We highly recommend using the HTTP return codes, as a code exists for every common case, which everybody understands. Of course, using the whole collection of codes is not necessary, usually the top-10 most used codes are enough.

200 OK is the usual success code for most cases. It is especially used when the first GET request on a resource is successful.

| HTTP Status | Description |

| 201 Created | Indicates that a resource has been created. Typical answer to PUT and POST requests, including a HTTP Header “Location” which points toward the new resource URL. |

| 202 Accepted | The request has been accepted and will be processed later. It is a classic answer to asynchronous calls (for better UX or performances). |

| 204 No Content | The request has been successfully processed, but there is nothing to return. It is often returned to a DELETE request. |

| 206 Partial Content | The content returned is incomplete. Mostly returned by paginated answers. |

HTTP StatusDescription400 Bad RequestCommonly used for calling errors if no other status matches. We can distinguish between two error types:Request behaviour error

GET /users?payed=1

< 400 Bad Request

< {"error": "invalid_request", "error_description": "There is no ‘payed' property on users."}

Application condition error

POST /users

{"name":"John Doe"}

< 400 Bad Request

< {"error": "invalid_user", "error_description": "A user must have an email address"}

401 UnauthorizedI do not know your id. Tell me who you are and I will check your authorizations.

| 1 2 3 | GET /users/42/orders < 401 Unauthorized < {"error": "no_credentials", "error_description": "This resource requires authorization, you must be authenticated and have the correct rights to access it" } |

403 ForbiddenYou are identified, but you do not have the necessary authorizations.

GET /users/42/orders

< 403 Forbidden

< {"error": "not_allowed", "error_description": "You're not allowed to perform this request"}

404 Not FoundThe resource you asked for does not exist.

GET /users/999999/

< 400 Not Found

< {"error": "not_found", "error_description": "The user with the id ‘999999' doesn't exist" }

405 Method not allowedEither calling a method on this resource has no meaning, or the user is not authorized to make this call.

POST /users/8000

< 405 Method Not Allowed

< {"error":"method_does_not_make_sense", "error_description":"How would you even post a person?"}

406 Not AcceptableNothing matches the Accept-* Header of the request. As an example, you ask for an XML formatted resource but it is only available as JSON.

GET /usersAccept: text/xmlAccept-Language: fr-fr

< 406 Not Acceptable

< Content-Type: application/json

< {"error": "not_acceptable", "available_languages":["us-en", "de", "kr-ko"]}

HTTP StatusDescription

| 500 Server error | This request is correct, but an execution problem has been encountered. The client cannot really do much about this. We recommend to systematically return a Status 500.<br><br><br>GET /users<br>< 500 Internal server error<br>< Content-Type: application/json<br>< {"error":”server_error", "error_description":"Oops! Something went wrong..."}<br> |

// ]]>o